Tags

Bottled Up, cinema, dramas, drug addiction, drug smuggling, dysfunctional family, enabling, Enid Zentelis, environmentalists, film reviews, films, Fredric Lehne, independent films, indie films, Jamie Harrold, Josh Hamilton, Marin Ireland, Melissa Leo, mother-daughter relationships, Movies, Nelson Landrieu, parent-child relationships, pill addiction, romances, Sam Retzer, Tibor Feldman, Tim Boland, writer-director

In an era when so many films seem to fulfill no greater need than increasing some conglomerate’s bottom line, it’s always refreshing to run across movies that actually have something to say, regardless of whether they have the expense account to say it loudly enough to get noticed. As someone who wearies of the “bigger, louder, dumber” mantra that rules the multiplex, I make a point to seek out the quieter, more modest choices whenever possible. After all: which type of film could really use more support…the billion-dollar tentpole flick or the indie that was probably made for a third of the former’s catering budget?

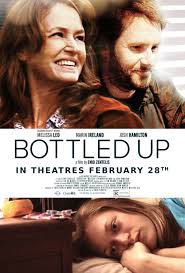

This, of course, ends up being quite the over-simplification but it helps put us in the proper mind to discuss writer-director Enid Zentelis’ Bottled Up (2013). Zentelis’ drug addiction drama, the follow-up to her debut, Evergreen (2004), is just the aforementioned kind of modest indie drama that normally fits my sensibilities like a glove. It’s the kind of film that I normally have no problem championing, usually over the top of something with a much larger advertising budget. In this case, however, I find myself in a bit of a pickle: you see, Bottled Up has its heart in the right place but the film is so fundamentally awkward that it’s difficult to ever become fully invested. That being said, I’ll gladly take a dozen well-intentioned films like this over much of the soulless superhero drivel and remakes that currently glut the multiplexes.

At its heart, Bottled Up is the story of Fay (Melissa Leo) and her adult daughter, Sylvie (Marin Ireland). Sylvie is a pill addict, supposedly the result of a car accident that screwed up her back, while her mother officially holds the title of “world-class enabler.” While Fay is a hard-working, responsible and caring individual, Sylvie is a complete wreck: manic, an habitual liar, an unrepentant thief and constantly in search of her next fix, Sylvie is like a human-shaped albatross perpetually affixed to her poor mother’s neck. Despite being “in control” of her daughter’s pain pills, Fay really isn’t in control of anything: whenever Sylvie feels like it, she just steals more money or hocks more shit, keeping her sleazy dealer, Jerry (Jamie Harrold), on speed-dial the whole while.

Just when things seem to be at their bleakest for Fay, she strikes up a friendship with Becket (Josh Hamilton), the spacey environmental activist who works at the local organic grocery store. Becket recycles, he composts, he takes samples of the local lake water and sends them to the government for testing and, most importantly, he seems to be swooning over Fay. Despite some obvious chemistry between the activist and the mom, however, Fay actually has different plans for Becket: believing that all Sylvie needs to “fix” her is the love of a good man, Fay does her damnedest to set the two up, despite her daughter’s near pathological desire to fuck it all up. As Fay keeps trying to “weld” Becket and Sylvie together, despite their overwhelmingly awkward interactions, she must also fight down her own growing feelings for the sensitive treehugger.

As is often the case, balance becomes a problem: how does one live their own life when they’re also living someone else’s? Fay continues to negotiate this precarious tightrope act, all while the local doctors get wise to Sylvie’s abuse issues and begin to make life even more difficult for the put-upon mother. Add one all-too-eager drug dealer, a spontaneous trip to Canada and growing self-awareness to the mix and you have yourself the recipe for some cathartic, if painful, personal growth. Will Fay finally discover who she really is or will Sylvie’s addiction wind up destroying everyone around her?

All of the elements are in place for Bottled Up to do exactly what it seems to set out to do. Yet, for various reasons, the film ends up feeling oddly flat and rather awkward. All of the principals – Melissa Leo, Marin Ireland and Josh Hamilton – have been responsible for some excellent performances in the past (Leo, in particular). Here, however, none of them seem to gel together, making much of the romantic angle feel forced and, at times, a little creepy. The ways in which Fay tries to push Becket and Sylvie together have a kind of whimsical “meet-cute” feel, at first, but quickly give way to something more awkward and cringe-worthy. Likewise Becket’s romancing of Fay: while it sometimes hits genuinely “sweet” moments, it all too often feels forced and out-of-place.

While Leo manages to get several very nice scenes and emotional moments (despite being saddled with an unfortunate haircut that spends the majority of the film obscuring her face), Ireland’s performance is almost uniformly awkward and strange. I get that Sylvie is a drug addict, many of whom are known to be rather squirrely individuals. Ireland’s performance is so erratic and wild, however, that it’s often difficult to figure out what which of the traits are the character’s and which are the actor’s. At numerous points, a sly look from Sylvie would seem to telegraph something only to amount to nothing: at a certain point, I was positive that Sylvie was trying to make Becket sick although, as I think about it later, it really wouldn’t make sense, under that context.

For his part, Hamilton plays Becket with such a blase, befuddled sense of inattention that, like with Ireland’s performance, it becomes a bit of a question as to what’s intended and what’s not. While the world is full of oblivious, tunnel-visioned individuals, surely none of them could be as absolutely blind to their immediate surroundings as Becket is: it’s not so much that he seems to be obsessed with the lake as that he seems to be willfully ignoring the highly dysfunctional mother-daughter team before him.

Part of the problem with the film’s overall impact is the disparity between some of the obviously whimsical elements and the more grim, overall feel. The score, courtesy of Tim Boland and Sam Retzer, is what I like to call “indie quirky” and the film features such magical-realist elements as Fay’s workplace, the bizarrely esoteric Mailboxes and Thangs (where one can mail a package, buy a donut and get a nipple piercing, all in the same visit). At times, Bottled Up seems one quirky character or cleverly placed indie tune away from the same patch of land where Wes Anderson normally builds his brand of particularly baroque architecture.

These lighthearted touches, however, end up sitting uncomfortably next to the film’s more unrelentingly dark, rather hopeless tone. Despite any of its issues, Bottled Up manages to be rather on-the-nose when it comes to depicting the humiliating, pointless and painful lives that addicts (and their families) suffer through: while the film never wallows in the shit-and-piss ugliness of something like Trainspotting (1996) or Requiem for a Dream (2000), there’s also nothing wholesome, cute or heartwarming about Fay and Sylvie’s relationship. More than anything, there’s a thick air of hopeless defeat that hangs over the characters: it feels as if we’ve entered Fay and Sylvie’s story at the very end, after both parties have, for all intents and purposes, given up. You always need a rock bottom in any recovery story, of course, but the constant emotional back-and-forth feels schizophrenic rather than organic.

Despite the aforementioned problems and the constant sense of awkward distance, there was still a lot to like here. While she doesn’t always hit the mark, Leo turns in another typically sturdy performance: Fay’s character does go through an arc, over the course of the story, and Leo is an assured pro at letting this comes across organically, rather than conveniently. I also really liked the film’s more loopy elements and wish Zentelis had opted to center more of the story there: there’s endless, virtually unexploited potential in the Mailboxes and Thangs concept, alone, not to mention Fay’s tentative steps into the world of conservationism. I also liked the concept of Jerry, the drug dealer, even if the actual character ended up being under-used and seemed to exit the film all too quickly. While the film is about Fay and Sylvie’s struggles, it also works best when it grounds them within the surrounding community.

At the end of the day, Bottled Up is a film with the very best intentions which, as I’ve stated earlier, certainly isn’t lost on me. Even if the various elements never cohere, it’s quite plain that Zentelis does have plenty of good insights into addiction, co-dependence and dysfunctional relationships. There are moments in the film that ring absolutely true and the final resolution is the kind of hopeful break in the storm clouds that really drives a film like this home. Bottled Up is an ode to addicts and the people who love them, even at the expense of their own individuality. I might not agree with how Zentelis said it, but I’ll damned if I can find much fault with what she had to say.